|

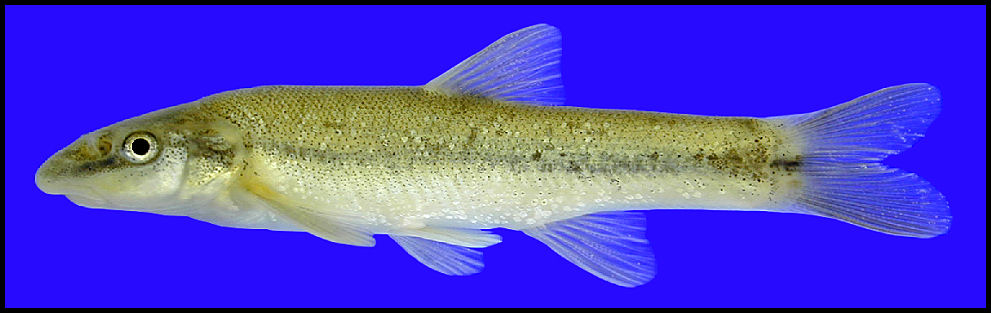

Picture by Chad Thomas, Texas State University-San Marcos |

||

|

Rhinichthys cataractae longnose dace

Type Locality Niagra Falls, New York (Valenciennes in Cuvier and Valenciennes 1842).

Etymology/Derivation of Scientific Name Rhino – snout, ichthys – fish, referring to prominent snout; cataractae – of cataracts, referring to Niagra falls, type locality (Scharpf 2005).

Synonymy Gobio cataractae Valenciennes in: Cuvier and Valenciennes 1842:315.

Characters Maximum size: 160 mm (6.30 in) TL (Page and Burr 1991).

Coloration: Olive-brown to dark red-purple above, brown-black spots and mottling on back and side of some individuals; dark stripe along side (darkest on young); dusky caudal spot; silver to yellow below; in populations occurring east of the Continental Divide, breeding male has bright red on corners of the mouth, cheeks, and bases of the paired and anal fins (Page and Burr 1991). Peritonium is silvery speckled with brown (Goldstein and Simon 1999).

Counts: Fewer than 10 dorsal fin soft rays (Hubbs et al. 2008). Pharyngeal teeth 2,4-4,2; 48-76 lateral line scales; 7-9 (usually 8) anal fin soft rays; 8 dorsal fin soft rays (Page and Burr 1991).

Mouth position: Subterminal (Goldstein and Simon 1999).

Body shape: No information at this time.

Morphology: Premaxillaries not protractile; upper lip connected with skin of snout by a frenum; distance from anal fin origin to end of caudal peduncle goes 2.5 or fewer times in distance from tip of snout to anal fin origin (Hubbs et al. 2008). Ratio of digestive tract (DT) to total length (TL): DT 0.6-0.8 TL; intestine is simple S-shaped loop (Goldstein and Simon 1999). Intestine not wound spirally around the gas bladder (Hubbs et al. 2008).

Distribution (Native and Introduced) U.S. distribution: Inhabits a wide area of North America; range extends south along the Rio Grande and Pecos River in New Mexico and extends into Texas throughout the Rio Grande to about Loredo (Hubbs et al. 2008).

Texas distribution: Rio Grande drainage (Hubbs et al. 2008).

Abundance/Conservation status (Federal, State, NGO) Special Concern (Hubbs et al. 2008). Currently Stable (Warren et al. 2000) in the Southern United States. Platania (1991) reported that R. cataractae was one of the four most abundant species collected from the Rio Chama and upper Rio Grande, New Mexico. Contreras-Balderas (1974) listed R. cataractae as one of the vanishing species of the Rio Conchos at Camargo, Mexico.

Habitat Associations Macrohabitat: Creeks, small to medium rivers; lakes (Gilbert and Shute 1980; Page and Burr 1991).

Mesohabitat: Normally common in swift streams with gravel beds, occasionally taken in lakes and clear pools of rivers (Gilbert and Shute 1980). Common in riffle habitats on the Atlantic slope; found in turbid, swift waters in upper Great Plains (Gilbert and Shute 1980). Brazo et al. (1978) reported that species preferred gravel-rock substrates, in Lake Michigan. In Little Sandy Creek, Pennsylvania, adults were usually collected in the lower portion of riffles; immature specimens were abundant in shallow pools (Reed 1959). In the Horse Creek drainage, eastern Wyoming, Rhinichthys cataractae biomass was primarily related to submerged aquatic vegetation, main channel run habitat, and overhead cover features (Hubert and Rahel 1989). In Michigan (confluence of Twomile Creek and the Ford River), adults were found in areas with faster currents and boulders in a higher proportion than juveniles; however, both adults and juveniles used areas with faster currents and boulders in a higher proportion than they occurred in the riffles at large; both sizes selected similar habitats but adults were more selective than juveniles, resulting in habitat segregation (Mullen and Burton 1995). Experimental tests of intraspecific competition in stream riffles indicated that both adult and juvenile fish use fast (40-50 cm/s) and medium (25-35 cm/s) velocity habitats while avoiding slow-velocity (0-10 cm/s) habitats; juveniles reduced use of shelters when adults were present, and expanded niches to include faster velocity areas of the riffle when adults were absent; juveniles did not increase use of larger substrates in the absence of adults; apparently segregation of juveniles and adults according to velocity is due to intraspecific competion for faster velocity areas within the riffle, while segregation according to substrate size may be due to an increasing preference for larger substrate as fish grow (Mullen and Burton 1998).

Biology Spawning season: In the spring (Gilbert and Shute 1980). Data indicated that females collected in June had begun spawning in North Carolina (Roberts and Grossman 2001). Mid-May through late July, in Lake Michigan; peak spawning periods occurred during late June and early July at water temperatures ranging between 14-19°C (Brazo et al. 1978). Late April to mid-June; in Wisconsin, peak spawning occurred in early May at an average water temperature of 17.2°C (range between 11.1-23.3°C (Becker 1983).

Spawning habitat: In streams and along the shoreline of lakes; deposits eggs among gravel or rarely in nests of other cyprinids (spawning in nests may occur when the attending male abandons the nest; Auer 1982).

Spawning behavior: Nonguarder; open substratum spawner; lithopelagophil – rock and gravel spawner with pelagic free embryos (Simon 1999). Populations occurring east of the Continental Divide spawn during the day, while populations in the Pacific basin spawn at night (Page and Burr 1991). In North Carolina, females apparently spawned more than once during the reproductive season (Roberts and Grossman 2001).

Fecundity: In Montana, females laid 200-1200 transparent, adhesive eggs that hatched in 7-10 days at 15.6°C (Gilbert and Shute 1980). In North Carolina, mean (±SD) potential fecundity differed significantly between females collected in March (1,832±572 oocytes; range 1155-2534) and those captured in June (775±415 oocytes; range 246-1653); females appeared potentially capable of spawning 6+ clutches per year; maximum oocyte diameter was 1.6 mm (Roberts and Grossman 2001). In Lake Michigan, egg production ranged from 870-9,953 eggs per female (Brazo et al. 1978). Becker (1983) examined Wisconsin specimens collected in early May: a 103 mm fish contained 181 ripe eggs, and a 99 mm fish held 655 ripe eggs; egg diameters ranged from 1.5-1.7. Mean egg diameter 1.6 mm (Coburn 1986). Auer (1982) listed information reported for Rhinichthys cataractae eggs: demersal, adhesive; diameter 2.1-2.7 mm; yolk amber, oil globule absent; incubation period 3-4 days at 18-24°C, and 6 days at 18°C.

Age/size at maturation: In North Carolina, smallest mature female captured was 56 mm SL (age 1+; Roberts and Grossman 2001). In Lake Michigan, a few fish spawned at age 1; all fish were mature by age 2 (Brazo et al. 1978). In Minnesota, both sexes attained maturity after two years of life, or in the third summer of life, when the individual is approximately 75 mm TL (Kuehn 1949).

Migration:

Growth and Population structure: In Lake Michigan, age 0 fish collected in late summer attained a mean length of 42 mm TL (range 32-54) by late October (Brazo et al. 1978). Brazo et al. (1978) reported mean total lengths for specimens collected from lake Michigan in 1975 and 1976: in 1975, mean total length for age 0 fish was 37.0 mm, 73.2 mm for age 1 fish, 87.1 mm (males) and 94.1 mm (females) for age 2 fish, 100 mm (males) and 111.8 mm (females) for age 3 fish, and 133.5 mm (males) and 117.4 mm (females) for age 4 fish; in 1976, mean total length for age 0 fish was 33.9 mm, 65.3 mm for age 1 fish, 93.2 mm (males) and 97.0 mm (females) for age 2 fish, 107.3 mm (males) and 112.0 mm (females) for age 3 fish, 126.8 mm (females) for age 4 fish, and 138 mm (females) for age 5 fish. Reed and Moulton (1973) reported back calculated total length for two Massachusetts populations: Ironstone Brook specimens were 53 mm TL at age class 1, and 71 mm, 87 mm, 99 mm, and 118 mm TL at age classes 2-5, respectively; West Branch Swift River specimens were 52 mm TL at age class 1, and 68 mm, 91 mm, 105 mm, and 119 mm TL at age classes 2-5, respectively; females exceeded males in growth by age class 3+. In Little Sandy Creek, Pennsylvania, age 1+ specimens ranged from 48-66 mm TL, age 2+ specimens ranged from 64-84 mm TL, age 3+ specimens ranged from 74-92 mm TL, age 4+ specimens ranged from 82-100 mm TL, and age 5+ specimens ranged from 94-118 mm TL (Reed 1959).

Longevity: 4 years in males and 5 years in females (Kuehn 1949; Reed and Moulton 1973).

Food habits: Invertivore; bottom feeder (Goldstein and Simon 1999). Main food items included 90% adult or immature stages of simulids, chironomids, and ephemerids (blackflies, midges and mayflies; Reed 1959; Goldstein and Simon 1999). Diet of Minnesota specimens collected in June almost entirely insectivorous, individuals consuming mainly Chironomids, Ephemerids, and Simulids in their immature stages (Kuehn 1949). Common food items found in Lake Michigan specimens were terrestrial insects and fish eggs (Brazo et al. 1978). In Montana, algae had highest frequency occurrence in specimens of the 0-49 mm length class, Tenedipedidae was highest in the 50-69 mm group, and Baetidae and Tendipedidae were equally high in the 70-100 mm group (Gerald 1966). In central Wisconsin, this species is primarily a dipteran feeder (Becker 1983). Thompson et al. (2001) examined response of this predatory, benthic species in a southern Appalachian stream to patchiness in the distribution of benthic macroinvertebrates on cobbles at three hierarchial spatial scales during summer, autumn and spring periods; results demonstrated that both spatial and temporal patchiness in resource availability significantly influenced use of both foraging patches and stream reaches by this species.

Phylogeny and morphologically similar fishes Natural hybridization between Rhinichthys cataractae and Gila pandora (Rio Grande chub) reported (Cross and Minckley 1960; Suttkus and Cashner 1981); and natural hybridization between R. cataractae and (Campostoma anomalum (central stoneroller) reported (Auer 1982).

See Cooper (1980) and Auer (1982) for description of egg, larval, and juvenile development, and Fuiman et al. (1983) for diagnostic characters of larval fish.

Host Records Species reported to normally have few parasites (Gilbert and Shute 1980).

Commercial or Environmental Importance

[Additional literature noting collection of this species from Texas locations includes, but is not limited to the following: Platania (1990); Edwards et al. (2002).]

References Auer, N.A. (ed.) 1982. Identification of larval fishes of the Great Lakes basin with emphasis on the Lake Michigan drainage. Great Lakes Fishery Commission, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Special Pub. 82-3:744 pp. Bartnik, V.G. 1970. Reproductive isolation between two sympatric dace, Rhinichthys atratulus and R. cataractae, in Manitoba. J. Fish. Res. Bd. Can. 27(2):2125-2141. Becker, G.C. 1983. Fishes of Wisconsin. The University of Wisconsin Press, Madison. 1052 pp.

Brazo, D.C, C.R. Liston, and R.C. Anderson. 1978. Life history of the longnose dace, Rhinichthys cataractae, in the surge zone of eastern Lake Michigan near Ludington, Michigan. Trans. Amer. Fish. Soc. 107(4):550-556.

Coburn, M.M. 1986. Egg diameter variation in eastern North American minnows (Pisces: Cyprinidae): correlation with vertebral number, habitat, and spawning behavior. Ohio Journal of Science 86:110-120.

Contreras-Balderas, S. Speciation aspects and man-made community composition changes in Chihuahuan Desert fishes. pp. 405-431 in: R.H. Wauer and D.H. Riskind (eds.) Transactions of the Symposium on the Biological Resources of the Chihuahuan Desert Region, United States and Mexico October 17-18, 1974, Sul Ross State University, Alpine Texas.

Cooper, J.E. 1980. Egg, larval, and juvenile development of longnose dace, Rhinichthys cataractae, and river chub, Nocomis micropogon, with notes on their hybridization. Copeia 1980(3):469-478.

Cross, F.B. and W.L. Minkley. 1960. Five natural hybrid combinations in minnows (Cyprinidae). University of Kansas Publications Museum of Natural History. 13(1):1-18.

Cuvier, G., and A. Valenciennes. 1842. Histoire Naturelle des Poissons 16:1-472. Paris.

Edwards, R.J., G.P. Garrett, and E. Marsh-Matthews. 2002. Conservation and status of the fish communities inhabiting the Conchos basin and middle Rio Grande, Mexico and U.S.A. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries 12:119-132.

Fuiman, L.A., J.V. Conner, B.F. Lanthrop, G.L. Buynak, D.E. Snyder, and J.J. Loos. 1983. State of the art of identification for cyprinid fish larvae from eastern North America. Trans. Amer. Fish. Soc. 112(2):319-332.

Hubbs, C., R.J. Edwards, and G.P. Garrett. 2008. An annotated checklist of the freshwater fishes of Texas, with keys to identification of species. Texas Journal of Science, Supplement, 2nd edition 43(4):1-87.

Hubert, W.A., and F.J. Rahel. 1989. Relations of physical habitat to abundance of four nongame fish in high-plains streams: a test of habitat suitability index models. North American Journal of Fisheries Management 9(3):332-340.

Gerald, J.W. 1966 Food habits of the longnose dace, Rhinichthys cataractae. Copeia 1966(3):478-485. Gilbert, C.R., and J.R. Shute. 1980. Rhinichthys cataractae (Valenciennes), Longnose dace. pp. 353 in D. S. Lee et al., Atlas of North American Freshwater Fishes. N. C. State Mus. Nat. Hist., Raleigh, i-r+854 pp. Goldstein, R.M., and T.P. Simon. 1999. Toward a united definition of guild structure for feeding ecology of North American freshwater fishes. pp. 123-202 in T.P. Simon, editor. Assessing the sustainability and biological integrity of water resources using fish communities. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida. 671 pp. Kuehn, J.H. 1949. A study of a population of longnose dace (Rhinicthys c. cataractae). Minnesota Academy of Sciences 17:81-87. Mullen, D.M., and T.M. Burton. 1995. Size-related habitat use by longnose dace (Rhinichthys cataractae). American Midland Naturalist 133(1):177-183. Mullen, D.M., and T.M. Burton. 1998. Experimental tests of intraspecific competition in stream riffles between juvenile and adult longnose dace (Rhinichthys cataractae). Canadian Journal of Zoology 76(5):855-862.

Page, L. M., and B. M. Burr. 1991. A field guide to freshwater fishes of North America north of Mexico. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, Massachusetts. 432 pp.

Platania, S.P. 1990. The ichthyofauna of the Rio Grande drainage, Texas and Mexico, from Boquillas to San Ygnacio. Report submitted to U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service: 100 pp.

Platania, S.P. 1991. Fishes of the Rio Chama and upper Rio Grande, New Mexico, with preliminary comments on their longitudinal distribution. Southwestern Naturalist 36(2):186-193.

Reed, R. 1959. Age, growth, and food of the longnose dace, Rhinichthys cataractae, in northwestern Pennsylvania. Copeia 1959(2):160-162.

Reed, R.J., and J.C. Moulton. 1973. Age and growth of the blacknose dace, Rhinichthys atratulus and longnose dace, R. cataractae in Massachusetts. American Midland Naturalist 90(1):206-210.

Roberts, J.H., and G.D. Grossman. 2001. Reproductive characteristics of female longnose dace in the Coweeta Creek drainage, North Carolina, USA. Ecology of Freshwater Fish 10:184-190.

Scharpf, C. 2005. Annotated checklist of North American freshwater fishes including subspecies and undescribed forms, Part 1: Petromyzontidae through Cyprinidae. American Currents, Special Publication 31(4):1-44. Simon, T. P. 1999. Assessment of Balon’s reproductive guilds with application to Midwestern North American Freshwater Fishes, pp. 97-121. In: Simon, T.L. (ed.). Assessing the sustainability and biological integrity of water resources using fish communities. CRC Press. Boca Raton, Florida. 671 pp. Suttkus, R.D., and R.C. Cashner. 1981. The intergeneric hybrid combination, Gila pandora X Rhinichthys cataractae (Cyprinidae), and comparisons with parental species. Southwestern Naturalist 26(1):78-81. Thompson, A.R., J.T. Petty, and G.D. Grossman. 2001. Multi-scale effects of resource patchiness on foraging behaviour and habitat use by longnose dace, Rhinichthys cataractae. Freshwater Biology 46:145-160.

Warren, M.L., Jr., B.M. Burr, S.J. Walsh, H.L. Bart, Jr., R.C. Cashner, D.A. Etnier, B.J. Freeman, B.R. Kuhajda, R.L. Mayden, H.W. Robison, S.T. Ross, and W.C. Starnes. 2000. Diversity, Distribution, and Conservation status of the native freshwater fishes of the southern United States. Fisheries 25(10):7-29.

|

||

|

|

||