|

|

||

|

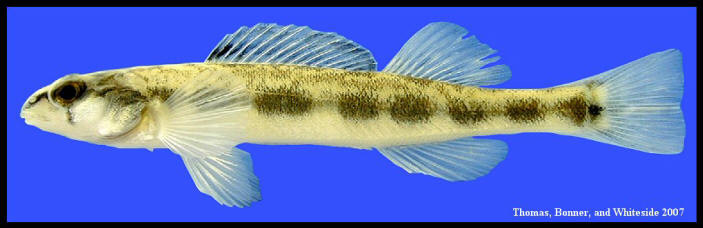

Percina maculata blackside darter

THIS ACCOUNT IS IN PROCESS. PLEASE CHECK BACK LATER FOR ADDITIONAL INFORMATION.

Type Locality Fort Gratiot, Lake Huron, Michigan (Girard 1860).

Etymology/Derivation of Scientific Name Percina – Latin diminutive of perca, “perch”; maculata – Latin maculatus, “spotted”, from macula, “spot” (Boschung and Mayden 2004).

Synonymy Alvordius maculatus Girard 1860:67. Alvordius aspro Hadropterus aspro Hadropterus maxinkuckiensis Hadropterus maculatus

Characters Maximum size: 110 mm TL (Page and Burr 1991).

Coloration: Sides with large black rectangular blotches (Hubbs et al. 2008). Discrete medial black caudal spot; prominent teardrop; olive above, wavy black lines, 8-9 dark saddles; 6-9 large oval black blotches along side; 1st dorsal fin dusky, black at front and along base (Page and Burr 1991). In the female, slaty shades intensify during the breeding season and appear somewhat browner than at other times; in males, color hues are intensely dark during the nuptial season (Petravicz 1938).

Counts: 61-76 lateral line scales (Hubbs et al. 2008).

Mouth position: Terminal (Goldstein and Simon 1999).

Body shape: Upper jaw reaches to pupil of eye; snout less conical, not extending beyond upper lip; body depth contained in standard length less than 7 times (Hubbs et al. 2008).

External morphology: Nape naked; upper lip connected to snout by a broad frenum; midline of belly with a series of enlarged scales or naked; preopercle smooth or weakly serrate (Hubbs et al. 2008). In the male, anterior flap of the ventral fin which contains the spine is sturdier and bulkier than in females, and the distal end and exterior border of the spine and the adjacent ray are very stout and crenate; the spread of male’s fin is also broader than that of the female (Petravicz 1938).

Internal morphology: See Branson and Ulrikson (1967) for information on morphology and histology of the branchial apparatus.

Distribution (Native and Introduced) U.S. distribution: Wide ranging species from the Great Lakes southwards through the Mississippi basin (Hubbs et al. 2008).

Texas distribution: Restricted to the Red River basin in the northeast part of the state (Hubbs et al. 2008).

Abundance/Conservation status (Federal, State, NGO) State Threatened (Texas; Hubbs et al. 2008). Currently Stable (Warren et al. 2000) in the southern United States. According to Page and Burr (1991), this species is one of the most common and widespread darters; however, it is seldom found in large populations (Page 1983). In Alabama, Percina maculata present in small numbers wherever found, but populations apparently unstressed (Boschung and Mayden 2004). Taylor et al. (2001) reported that this species had not been collected in Kinkaid Creek drainage, southern Illinois, since its impoundment in 1970 and P. maculata is believed to be extirpated from the drainage. Lindsey et al. (1983) suggested that this species was rarer in the Poteau River (Oklahoma and Arkansas) than it was in the past; the species was taken at 13 locations during collections in 1947, while no specimens were captured during a 1974 survey. In southeastern Oklahoma, Eley et al. (1981) compared abundance of this species in the Mountain Fork River both before and after its impoundment by Broken Bow Dam and reported that no specimens had been collected since impoundment.

Habitat Associations Macrohabitat: Small to medium rivers (Page and Burr 1991).

Mesohabitat: Often found in clear, gravelly streams, and taken in turbid (Ontario, Canada) streams (Beckham and Platania 1980); prefers pools with some current, or even quiet pools, to swift riffles. Found in slow-moving streams (Auer 1982). In the Des Moines River (Boone Co., Iowa), larger individuals were found in deeper, slower-moving water in pools, while smaller fish were usually found in shallow water associated with sand (Karr 1963). In the River Rouge (Belle Branch), southern Michigan, specimens were captured in depressions with bottom of sand and gravel during late spring and early summer (Petravicz 1938). During the non-breeding season, species occurred in deep, often silt-covered pools (Winn 1958a). In the Kaskaskis River, Illinois, species collected from pools and riffles; in riffles, it was found most often in the deeper places where the current decreased.; in one area, species was often collected around brush and logs where the current was slow (Thomas 1970). Specimens captured from Kincaid Creek, Illinois were collected from deep pools surrounded by debris (Stegman 1969). Trautman (1957) noted that the species frequented brush heaps and tree roots under cut-banks, especially as emergency cover; species found in moderate strands of water willow and pondweeds, especially young fish. Found in streams with substantial gravel, in southeastern Michigan (Diana et al. 2006). Hocutt et al. (1978) noted collection of specimens from sites on a stream (Greenbriar River, West Virginia) having excellent water quality. During May-September sampling of the Thames River watershed, southwestern Ontario, Canada, P. maculata was found mainly in pools or raceways; species was also observed in relatively quiet waters along the edge of riffles or behind large rocks (Englert and Seghers 1983).

Biology Spawning season: Spawning observed in May when water temperature was 16.5°C, in southern Michigan (Petravicz 1938). Spawning occurs during April and May, in Wisconsin (Lutterbie 1979). Early May to mid-June in Michigan and throughout the Great Lakes region (Auer 1982).

Spawning habitat: Eggs deposited in a depression of fine sand or gravel in water about 30 cm deep with moderate current (Petravicz 1938). Winn (1958a, 1958b) observed mating in streams in water 60 cm or more deep in pool or raceway-like areas over sand or gravel. Trautman (1948) reported spawning in streams of moderate gradient in pools with current over sand or gravel substrate, in Ohio.

Spawning behavior: Nonguarder; brood hider; lithophils – rock and gravel spawners that do not guard eggs (Simon 1999). Female usually initiates spawning act; after swimming to a desirable depression the female is pursued by males; when the female stops, a single male assumes a clasping position with her (male on female’s back; horizontal; Winn 1958a) the pair vibrate their bodies for several seconds while pressing the genital apertures of their vibrating bodies into the gravelly or sandy depression where eggs are deposited (Petravicz 1938); when spawning over sand, fish displace bottom material, thus forming a shallow depression; their motions are not strong enough to disturb gravel; the spawning act may be repeated after a period of rest lasting from 5-30 minutes; female spawns periodically (with several different males) from early morning until late afternoon and is usually spent within 2 ½ days (Petravicz 1938). Winn (1958a) described territorial defense as weakly interspecific around female, and territory as moderate-sized.

Fecundity: Winn (1958a) reported egg counts for 2 pre-spawning females (52 mm SL and 53 mm SL) ranging from 1,000-1,758, respectively; eggs large, colorless, about 2 mm in diameter. In the Kaskaskia River, Illinois, older females had gonads containing up to 2,000 eggs as early as March (Thomas 1970). Eggs adhesive, demersal, spherical, and 2 mm in diameter; minimum incubation period of 142 hours (incubation temperature not reported; Petravicz 1938).

Age at maturation: Usually after the first year (Winn 1958a). Thomas (1970) suggested that larger yearling females in the Kaskaskia River, Illinois, probably spawned, but that small yearling females had very small eggs and probably would not have spawned until after their first year.

Migration: Fish migrate upstream to breeding grounds (Winn 1958b). Enters riffles for spawning in the spring (Thomas 1970). Species is migratory (Trautman 1957; Thomas 1970); in the Kaskaskia River, Illinois, it was more abundant in the headwaters in winter and spring than in summer (Thomas 1970).

Growth and Population structure: In the Des Moines River, Iowa, calculated average total length at annulus was 34.7 mm TL at the first annulus, 50.9 mm at second annulus, 65.3 mm at third annulus, and 77.0 mm TL at fourth annulus (Karr 1963). In the Kaskaskia River, Illinois, year I fish averaged 50.9 mm TL, year II fish averaged 63.3 mm TL, year III fish averaged 69.4 mm TL, and year IV fish averaged 78.7 mm TL (Thomas 1970); most rapid growth in young fish occurred June –September. Calculated mean total lengths were reported for 128 specimens captured in Wisconsin: 46.5-47.8 mm at first annulus, 70-74 mm at second annulus, 80-95 mm at third annulus, and 92-108 mm TL at fourth annulus (Lutterbie 1979; Page 1983).

Longevity: 4 years (Karr 1963). Two individuals collected from the Kaskaskia River, Illinois in their fifth year of life (Thomas 1970).

Food habits: Invertivore; benthic (Goldstein and Simon 1999). In Ohio specimens, stomachs contained mayfly and midge larvae, copepods, corixid nymphs, and fish remains (Turner 1921; Beckham and Platania 1980). In the Des Moines River, Iowa, insects were the principle food (Diptera, Ephemeroptra, and Tricopter in order of importance), and crustaceans (Ostracoda) also occurred in the diet; the small stones and plant material that occurred in stomachs was probably ingested incidentally in normal feeding (Karr 1963). Food organisms found in Percina maculata from the Kaskaskia River, Illinois: Diptera, Ephemeroptera, Trichoptera, Coleoptera, Hemiptera, Crustacea, fish eggs, insect eggs, and plant material; species fed during daylight hours (Thomas 1970). Trautman (1957) observed feeding at the water surface.

Phylogeny and morphologically similar fishes Subgenus Alvordius (Page 1974; Beckham 1986). Percina maculata is often confused with P. sciera, which has a vertical row of 3 diffuse dark brown caudal spots, while P. maculata has a discrete medial black caudal spot (Page and Burr 1991). In Texas, P. maculata may be distinguished from P. sciera in that it has a longer jaw, no scales on the nape (extralimital P. maculata may have the nape scaled), and by the presence of a distinct roundish median black spot at the base of the caudal (Hubbs 1954).

Percina maculata known to hybridize with P. caprodes (logperch; Winn 1958a; Page 1976). Thomas (1970) reported hybrids of P. maculata and P. phoxocephala from the Kaskaskia River, Illinois; and Page (1976) reported another P. maculata X P. phoxocephala specimen from the Elk Fork Salt River. Etheostoma gracile (slough darter) X P. maculata hybrid collected from Dismal Creek, Illinois (Page 1976).

See Petravicz (1938) for description and illustration of newly hatched and 21 day-old post-larvae. Developmental characters described by Fish (1932).

Near (2002) studied phylogenetic relationships of Percina and proposed a classification of Percina, listing Percina maculata clade (P. maculata, P. notogramma, and P. pantherina).

Host Records Bangham and Hunter (1939) found one specimen from Lake Erie infected with the nematode Camallanus oxycephalus. Karr (1963) reported an individual from the Des Moines River, Iowa, having a leech of the family Piscicolidae on the base of the dorsal fin. The copepod, Lernea cyprinacea, was reported from a fish in Vigo County, Indiana (Demaree 1967). Thomas (1970) found specimens with external parasites in the Kaskaskia River, Illinois.

Commercial or Environmental Importance According to Trautman (1957), Percina maculata apparently highly intolerant to certain organic pollutants, such as mine waste.

References Auer, N.A. 1982. Identification of larval fishes of the Great Lakes basin with emphasis on the Lake Michigan drainage. Great Lakes Fishery Commission, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Special Publication 82-3:744 pp.

Bangham, R.V., and G.W. Hunter III. 1939. Studies on fish parasites of Lake Erie. Distribution studies. Zoologica 24(4):385-448. Beckham, E.C., and S.P. Platania. 1980. Percina maculata (Girard), Blackside darter. pp. 728 in D. S. Lee et al., Atlas of North American Freshwater Fishes. N. C. State Mus. Nat. Hist., Raleigh, i-r+854 pp.

Beckham, E.C. 1986. Systematics and redescription of the blackside darter, Percina maculata (Girard), (Pisces: Percidae). Occasional Papers of the Museum of Zoology, Louisiana State University, no. 62. Baton Rouge, La: Louisiana State University. Boschung, H.T., Jr., and R.L. Mayden. 2004. Fishes of Alabama. Smithsonian Books, Washington. 736 pp. Branson, B.A., and G.U. Ulrikson. 1967. Morphology and histology of the branchial apparatus in percid fishes of the genera Percina, Etheostoma, and Ammocrypta (Percidae: Percinae: Etheostomatini). Transactions of the American Microscopical Society 86(4):371-389. Demaree, R.S., Jr. 1967. Ecology and external morphology of Lernea cyprinacea. American Midland Naturalist 78(2):416-427. Diana, M., J.D. Allan, and D. Infante. 2006. The influence of physical habitat and land use on stream fish assemblages in southeastern Michigan. American Fisheries Society Symposium 48:359-374. Dieterman, D.J., and C.R. Berry. 2000. Summer habitat associations of rare fishes in South Dakota tributaries to the Minnesota River. Proceedings of the South Dakota Academy of Science 79:103-112. Eley, R., J. Randolph, and J. Carroll. 1981. A comparison of pre- and post-impoundment fish populations in the Mountain Fork River in southeastern Oklahoma. Proc. Okla. Acad. Sci. 61:7-14. Englert, J., and B.H. Seghers. 1983. Habitat segregation by stream darters (Pisces: Percidae) in the Thames River watershed of southwestern Ontario. Canadian Field-Naturalist 97(2):177-180. Fish, M.P. 1932. Contributions to the early life histories of sixty-two species from Lake Erie and its tributary waters. Bulletin of the United States Bureau of Fisheries 47:293-398. Girard, C.F. 1860. Ichthyological notices. Proc. Acad. Nat. Sci. Phila. [1859] 11:56-68. Goldstein, R.M., and T.P. Simon. 1999. Toward a united definition of guild structure for feeding ecology of North American freshwater fishes. pp. 123-202 in T.P. Simon, editor. Assessing the sustainability and biological integrity of water resources using fish communities. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida. 671 pp. Hocutt, C.H., R.F. Denoncourt, and J.R. Stauffer, Jr. 1978. Fishes of the Greenbriar river, West Virginia, with drainage history of the central Appalacians. Journal of Biogeography 5:59-80. Hubbs, C. 1954. A new Texas subspecies, apristis, of the darter Hadropterus scierus, with a discussion of variation within the species. American Midland Naturalist 52(1):211-220.

Hubbs, C., R.J. Edwards, and G.P. Garrett. 2008. An annotated checklist of the freshwater fishes of Texas, with keys to identification of species. Texas Journal of Science, Supplement, 2nd edition 43(4):1-87.

Karr, J.R. 1963. Age, growth, and food habits of Johnny, slenderhead and blackside darters of Boone County, Iowa. Iowa Acad. Sci. 70:228-236.

Lindsey, H.L., J.C. Randolph, and J. Carroll. 1983. Updated survey of the fishes of the Poteau River, Oklahoma and Arkansas. Proc. Okla. Acad. Sci. 63:42-48.

Near, T.J. 2002. Phylogenetic relationships of Percina (Percidae: Etheostomatinae). Copeia 2002(1):1-14.

Lutterbie, G.W. 1979. Reproduction and growth in Wisconsin darters (Osteichthyes: Percidae). Reports on the Fauna and Flora of Wisconsin, University of Wisconsin, Stevens Point. 44 pp.

Page, L.M. 1974. The subgenera of Percina (Percidae: Etheostomatini). Copeia 1974(1):66-86.

Page, L.M. 1976. Natural darter hybrids: Etheostoma gracile X Percina maculata, Percina caprodes X Percian maculata, and Percina phoxocephala X Percina maculata. The Southwestern Naturalist 21(2):161-168.

Page, L.M. 1983. Handbook of Darters. TFH Publications, Inc. Ltd., Neptune City, New Jersey. 271 pp.

Page, L.M., and B.M. Burr. 1991. A field guide to freshwater fishes of North America north of Mexico. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, Massachusetts. 432 pp.

Petravicz, W.P. 1938. The breeding habits of the black-sided darter, Hadropterus maculatus Girard. Copeia 1938(1):40-44. Simon, T. P. 1999. Assessment of Balon’s reproductive guilds with application to Midwestern North American Freshwater Fishes, pp. 97-121. In: Simon, T.L. (ed.). Assessing the sustainability and biological integrity of water resources using fish communities. CRC Press. Boca Raton, Florida. 671 pp. Stegman, J.L. 1969. Fishes of Kincaid Creek, Illinois. Transactions of the Illinois State Academy of Science 52(1/2):25-32. Taylor, C.A., J.H. Knouft, and T.M. Hiland. 2001. Consequences of stream impoundment on fish communities in a small North American drainage. Regulated Rivers: Research and Management 17:687-698. Thomas, D.L. 1970. An ecological study of four darter species of the genus percina (Percidae) in the Kaskaskia River, Illinois."Illinois Natural History Survey, Biological Notes 70:1-18. Trautman, M.B. 1948. A natural hybrid catfish, Schilbeodes miurus x Schilbeodes mollis. Copeia 1948(3):166-174. Trautman, M.B. 1957. Fishes of Ohio. The Ohio State University Press, Waverly Press, Inc., Baltimore, Maryland. 683 pp. Turner, C.L. 1921. Food of the common Ohio darters. Ohio J. Sci. 22(2):41-62.

Warren, M.L., Jr., B.M. Burr, S.J. Walsh, H.L. Bart, Jr., R.C. Cashner, D.A. Etnier, B.J. Freeman, B.R. Kuhajda, R.L. Mayden, H.W. Robison, S.T. Ross, and W.C. Starnes. 2000. Diversity, Distribution, and Conservation status of the native freshwater fishes of the southern United States. Fisheries 25(10):7-29.

Winn, H.E. 1958a. Comparative reproductive behavior and ecology of fourteen species of darters (Pisces-Percidae). Ecological Monographs 28(2):155-191. Winn, H.E. 1958b. Observation on the reproductive habits of darters (Pisces: Percidae). American Midland Naturalist 59(1):190-212. |

||

|

|

||