|

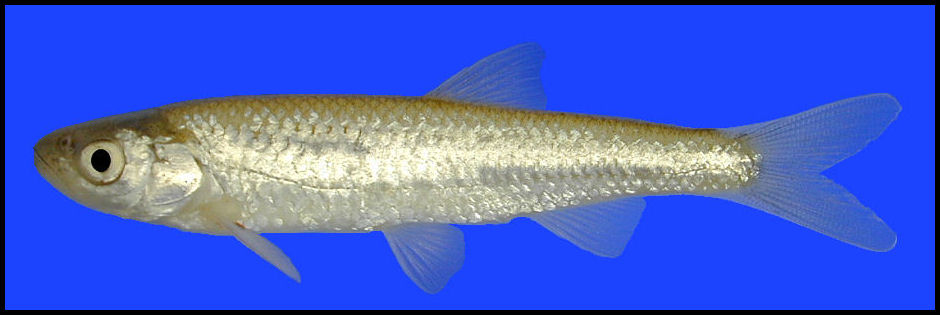

Picture by Chad Thomas, Texas State University-San Marcos |

||

|

Notropis jemezanus Rio Grande shiner

Type Locality Rio Grande, at San Ildefonso, about 16 km east of Los Alamos, Santa Fe Co., New Mexico (Cope in Cope and Yarrow 1875).

Etymology/Derivation of Scientific Name Notropis – ridged or keeled back; a misnomer, probably due to the shrunken specimen used by Rafinesque when establishing this genus for N. atherinoides; jemezanus – from Jemez Mountains, type locality (Scharpf 2005).

Synonymy Alburnellus jemezanus Cope and Yarrow 1875:650. Minnilus jemezanus Jordan and Gilbert 1883:203 (Sublette et al. 1990). Notropis dilectus Jordan and Evermann 1896-1900:259 (Sublette et al. 1990). Notropis jemezanus Knapp 1953:61.

Characters Maximum size: 75 mm (2.95 in) TL (Page and Burr 1991).

Coloration: Koster (1957) described coloration as mostly plain silvery, except for a faint dusky band. The head, back and abdomen are silvery; sides with dark lateral stripe; peritoneum silvery with a few dark specks, heavier dorsally; apex of chin and narrow anterior portion of gula densely covered with melanophores; upper jaw with scattered melanophores (Sublette et al. 1990). Lips may be dusky; black around anal fin base and along underside of caudal peduncle (Page and Burr 1991). Hubbs et al. (1991) listed the following characteristics for species in Texas: no chromatophores on lateral line scales other than on lateral stripe; middorsal stripe behind dorsal fin usually one or two chromatophores wide.

Pharyngeal teeth count: 1-2,4-4,2 or 1-4-4,1.

Counts: 40 or fewer lateral line scales; 24 or fewer predorsal scales; usually 9-12 anal fin soft rays (Knapp 1953; Hubbs et al. 1991); 7-8 dorsal fin soft rays; 14-15 pectoral fin soft rays; 8 pelvic fin soft rays; 19-20 caudal fin soft rays (Sublette et al. 1990).

Mouth position: Terminal and oblique (Hubbs et al. 1991).

Body shape: Slender, body depth less or equal to the head length in adult fish (Knapp 1953; Hubbs et al. 1991).

Morphology: Scales large; lower lip thin, without a fleshy lobe; lateral line either straight or with a broad arch; premaxillaries protractile; upper lip separated from skin of snout by a deep groove continuous across the midline (Knapp 1953; Hubbs et al. 1991). Eye small, contained about four times in body depth (measured over curve); origin of dorsal fin behind insertion of pelvic fins (Knapp 1953; Hubbs et al. 1991). Breeding males with many small tubercles on snout and most of dorsal portion of the head (Sublette et al. 1990). Intestinal canal short, forming a simple S-shaped loop (Knapp 1953; Hubbs et al. 1991).

Distribution (Native and Introduced) U.S. distribution: Endemic to Rio Grande drainage, from just above mouth of main river in Texas and Mexico to headwaters of Rio Grande and Pecos rivers, northern New Mexico; range also includes major tributaries in Mexico: Rio San Juan, Rio Salado and Rio Conchos (Gilbert 1980).

Texas distribution: Rio Grande drainage (Hubbs 1940; Hubbs 1957; Gilbert 1980; Hubbs et al. 1991).

[Additional literature noting collection of this species from Texas locations includes, but is not limited to the following: Contreras-Balderas et al. (2002).]

Abundance/Conservation status (Federal, State, Non-governmental organizations) Imperiled (Scharpf 2005); rare, Mexico (CONABIO 1997; Edwards et al. 2002; Scharpf 2005). Texas Organization for Endangered Species (1988) placed species on watch list. Williams et al. (1989) listed status for Notropis jemezanus as one of special concern due to factors including the present or threatened destruction, modification, or curtailment of habitat or range; and other natural or manmade factors affecting continued existence of the species. Hubbs et al. (1991) reported N. jemezanus as threatened in Texas and Edwards et al. (2002) report collections supporting this designation. They were reported as apparently common in the lower half of main Rio Grande (Robinson 1959; Gilbert 1980). Hubbs et al. (1977) reported absence of N. jemezanus from middle Rio Grande between El Paso and Presidio, Texas due to local irrigation practices and was ranked 20th in total abundance (0.18%) in collections from the Rio Grande drainage, Texas, between Boquillas and San Ygnacio (primarily occurred upstream of Amistad Reservoir); range and abundance noticeably diminished in the Rio Grande since the 1950s (Platania 1990). Edwards and Contreras-Balderas (1991) and Hubbs et al. (1991) noted decline of this species in recent years and spotty distribution within the Rio Grande Basin. In the Pecos River (Texas), N. jemezanus was virtually absent in samples taken from 1986-1988 after a red tide fish kill; prior to the kill they had been relatively abundant (Hubbs 1990; Rhodes and Hubbs 1992). This species has not been collected in Independence Creek since 1991 or in the lower Pecos River since 1987 (Hoagstrom 2003; Bonner et al. 2005); Linam and Kleinsasser (1996) reported capture of 16 specimens, all from the same site (Ose Canyon), during sampling of the Pecos River (Texas) and Independence Creek (Texas) in October 1987. In New Mexico, this species has been extirpated in the Rio Grande (Bestgen and Platania 1991; Platania 1991; Platania and Altenbach 1998). They persist in the Pecos River in New Mexico, though it has been extirpated from the 89 km reach of the Upper Pecos River between Santa Rosa and Sumner Reservoirs (Platania and Altenbach 1998). In the Pecos River, New Mexico (between Fort Sumner Irrigation District Dam and Brantley Reservoir), sampling conducted between 1992 and 2002 revealed that N. jemezanus composed 10.7% of all fish collected; this area harbors the largest known N. jemezanus population and is also the last remaining population within the Pecos River basin (Hoagstrom and Brooks 2005). According to Edwards et al. (2004), this species had not been collected below Amistad Reservoir in the last 10 years.

Habitat Associations Macrohabitat: Typically found in large rivers or creeks (Gilbert 1980).

Mesohabitat: Occurs over substrate of rubble, gravel and sand, often overlain with silt (Gilbert 1980); tends to prefer turbid water (Huber and Rylander 1992). In the Pecos River, New Mexico, they primarily selected mesohabitats with low to moderate velocities (backwaters and parallel plunges); N. jemezanus selected pools in winter and perpendicular plunge pools in summer (Kehmeier et al. 2007). In the Pecos River (New Mexico), age 0-1 fish had highest densities in downstream river stretches, presumably due to displacement of pelagic, semibuoyant embryos and early larvae; density of older fish was low in the same areas though the reasons are unclear (Hoagstrom and Brooks 2005). Young often found in Tornillo Creek, Texas in summer months (Hubbs and Wauer 1973).

Biology Spawning season: Presumably May-August (Hoagstrom and Brooks 2005); gravid females noted from collections made from mid-May to late-August (Sublette et al. 1990).

Spawning habitat: Wide river channels with loose shifting sand substrate (Hoagstrom and Brooks 2005).

Spawning behavior: Pelagic-broadcast spawner (Platania and Altenbach 1998). In aquaria, the following generalized spawning behavior was exhibited: males pursued a single female, nudging her abdominal region. When female was ready to spawn, a single male wrapped around female; eggs and milt were simultaneously expelled at this time. Reproductive process usually consisted of several individual spawning episodes with at least 10 minute intervals between events (Platania and Altenbach 1998).

Fecundity: Non-adhesive, semibuoyant eggs, ranging from 2.9-3.0 mm (.114-.118 in) in diameter (Platania and Altenbach 1998).

Age at maturation: No information at this time.

Migration: Hoagstrom and Brooks (2005) reported low density of older N. jemezanus in downstream river stretches, and noted that some authors have suggested that pelagic embryos and larvae displaced downstream eventually return upstream as juveniles or adults to maintain spawning populations, though this hypothesis is untested (Cross et al. 1985; Fausch and Bestgen 1997; Platania and Altenbach 1998; Bonner 2000).

Growth and Population structure: In collections made January-April (1st trimester) in the Pecos River (New Mexico), age 1 fish ranged from 10-46 mm (.39-1.81 in) SL and age 2+ fish ranged from 46-71 mm (1.81-2.80 in) SL; in May-August (2nd trimester) collections, age 0-1 (representing individuals in the same calendar year of their hatching) fish ranged from 9-32 mm (.35-1.26 in) SL, age 1 fish ranged from 29-49 mm (1.14-1.93 in) SL, and age 2+ fish ranged from 49-69 mm (1.93-2.72 in) SL; in collections made September-December (3rd trimester), age 0-1 fish ranged from 9-42 mm SL, age 1 fish ranged from 42-54 mm (1.65-2.13 in) SL, and age 2+ fish ranged from 54-62 mm (2.13-2.44 in) SL; age 0-1 fish dominated population between May and December, with age 1 dominant between January and April; age 1 fish also abundant between May and August, but less so between September and December; age 2+ fish were uncommon, yet present in all trimesters (Hoagstrom and Brooks 2005).

Longevity: Individuals survive at least 2 winters (Hoagstrom and Brooks 2005).

Food habits: The simple S-shaped gut indicates that species is primary carnivorous-omnivorous (Sublette et al. 1990).

Phylogeny and morphologically similar fishes Subgenus Notropis; the emerald shiner (Notropis atherinoides) and the sharpnose shiner (N. oxyryhnchus), also members of subgenus Notropis, occur within closest geographical range of N. jemezanus (Gilbert 1980). N. jemezanus similar to N. atherinoides, but has larger, less slanted mouth extending under eye while N. atherinoides has a more slanted mouth reaching to front of eye on fairly pointed snout; N. jemezanus has smaller eye; deeper snout; and lacks black lips (may be dusky) versus having the front half of lips black in coloration as does N. atherinoides; further, N. jemezanus has black around anal fin base and along underside of caudle peduncle (Page and Burr 1991). Phylogenetic analysis of cytochrome b indicated strong support for sister-group relationship between N. jemezanus and the Texas shiner (N. amabilis; Bielawski and Gold 2001). N. amabilis differs from N. jemezanus in having the eye distinctly longer than the snout and in having along the sides a dark streak that is separated from the dorsal pigmentation by a clear area (Koster 1957). See Amemiya and Gold (1988) for information related to the use of chromosomal NORs in differentiating N. jemezanus from other Notropis species, including N. amabilis.

Host Records No information at this time.

Commercial or Environmental Importance According to Propst et al. (1987), causes for the loss of Notropis jemezanus in the Rio Grande (New Mexico) by the mid 1960s were not distinct, but were probably related to deterioration and loss of mainstem, mid-channel fluvial habitats. Platania and Altenbach (1998) also noted that modification of historic hydrograph and fragmentation of the Middle Rio Grande may have lead to loss of species in this reach (Platania and Altenbach 1998).

References

Amemiya, C.T., and J.R. Gold. 1988. Chromasomal NORs as taxonomic and systematic characters in North American cyprinid fishes. Genetica 76:81-90.

Bestgen, K.R., and S.P. Platania. 1991. Status and conservation of the Rio Grande silvery minnow, Hybognathus amarus. The Southwestern Naturalist 36(2): 225-232.

Bielawski, J.P., and J.R. Gold. 2001. Phylogenetic relationships of cyprinid fishes in subgenus Notropis inferred from Nucleotide sequences of the mitochondrially encoded cytochrome b gene. Copeia 2001(3):656-667.

Bonner, T.H. 2000. Life history and reproductive ecology of the Arkansas River shiner and peppered chub in the Canadian River, Texas and New Mexico. Ph.D. dissertation, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas. 147 pp.

Bonner, T.H., C. Thomas, C.S. Williams, and J.P. Karges. 2005. Temporal assessment of a West Texas stream fish assemblage. The Southwestern Naturalist 50(1):74-106.

Comision Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (CONABIO) (1997) Oficio No. DOO.750,- 1415/97), la revision de la NOM-ECOL-059-1994, Norma Oficial Mexicana NOMECOL-059-1994, que determina las especies y subespecies del flora y fauna silvestres terrestres y acuaticas en peligro de extincion, amnazadas raras y las sujetas a proteccion especial y qu establece especificaciones para su proteccion, Publicada en el D.O.F. de fecha 16 de mayo de 1994.

Contreras-Balderas, S. R.J. Edwards, M.D. Lozano-Vilano, M.E. Garcia-Ramirez. 2002. Fish biodiversity changes in the lower Rio Grande/Rio Bravo, 1953-1996. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries 12:219-240.

Cope, E.D., and H.C. Yarrow. 1875. Report upon the collection of fishes made in portions of Nevada, Utah, California, Colorado, New Mexico, and Arizona during the years 1871-1874. Chapter 6, pp. 635-703. In: United States Army Engineers Dept. Report, in charge of George M. Wheeler. Geog. and Geol. of the Expl. and Surveys west of 100th meridian, 5, 1-1021.

Cross, F.B., R.E. Moss, and J.T. Collins. 1985. Assessment of dewatering impacts on stream fisheries in the Arkansas and Cimarron Rivers. Nongame Wildlife Contract No. 46. Kansas Fish Game Comm. Univ. Kans. (KU 5400-0705).

Edwards, R.J., G.P. Garrett, and E. Marsh-Matthews. 2002. Conservation and status of the fish communities inhabiting the Rio Conchos basin and middle Rio Grande, Mexico and U.S.A. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries 12:119-132.

Edwards, R.J., G.P. Garrett, and N.L. Allan. 2004. Aquifer-dependent fishes of the Edwards Plateau region. Chapter 13, pp. 253-268 in: Mace, R.E., E.S. Angle, and W.F. Mullican, III (eds.). Aquifers of the Edwards Plateau. Texas Water Development Board. 360 pp.

Edwards, R.J., and S. Contreras-Balderas. 1991. Historical changes in the ichthyofauna of the lower Rio Grande (Rio Bravo del Norte), Texas and Mexico. The Southwestern Naturalist 36(2):201-212.

Fausch, K.D., and K.R. Bestgen. 1997. Ecology and fishes indigenous to the central and southwestern Great Plains. Pp. 131-166, in: F.L. Knopf and F.B. Samson (eds.). Ecology and Conservation of Great Plains Vetebrates. Ecological Studies 125. Springer-Verlag New York, Inc. 320 pp.

Gilbert, C.R. 1980. Notropis jemezanus (Cope), Rio Grande shiner. p. 279. In: D. S. Lee, C. R. Gilbert, C. H. Hocutt, R. E. Jenkins, D. E. McAllister & J. R. Stauffer, Jr. (eds.), Atlas of North American freshwater fishes, North Carolina State Museum of Natural History, Raleigh, 854 pp.

Hoagstrom, C.W. 2003. Historical and recent fish fauna of the lower Pecos River. In G.P. Garrett and N.L. Allen, editors. Aquatic fauna of the Northern Chihuahuan Desert. Special Publications Number 46, Museum, Texas Tech University, Lubbock. Pp. 91-109.

Hoagstrom, C.W., and J.E. Brooks. 2005. Distribution and status of Arkansas River shiner Notropis girardi and Rio Grande shiner Notropis jemezanus, Pecos River, New Mexico. Texas Journal of Science 57(1):35-58.

Hubbs, C. 1957. Distributional patterns of Texas fresh-water fishes. The Southwestern Naturalist 2(2/3):89-104.

Hubbs, C. 1990. Status of the endangered fishes of the Chihuahuan Desert. Pp. 89-96. In: Proceedings of the Third Chihuahuan Desert Conference, Alpine, Texas.

Hubbs, C., and R. Wauer. 1973. Seasonal changes in the fish fauna of Tornillo Creek, Brewster County, Texas. The Southwestern Naturalist 17(4):375-379. Hubbs, C., R.J. Edwards, and G.P. Garrett. 1991. An annotated checklist of the freshwater fishes of Texas, with keys to identification of species. Texas Journal of Science, Supplement 43(4):1-56.

Hubbs, C., R. R. Miller, R. J. Edwards, K. W. Thompson, E. Marsh, G. P. Garrett, G. L. Powell, D. J. Morris, and R. W. Zerr. 1977. Fishes inhabiting the Rio Grande, Texas and Mexico, between El Paso and the Pecos confluence. Symposium on importance, preservation, and management of riparian habitat, Tucson, Arizona, 91-97.

Hubbs, C.L. 1940. Fishes from the Big Bend region of Texas. Transactions of the Texas Academy of Science 23:3-12.

Huber, R., and M.K. Rylander. 1992. Brain morphology and turbidity preference in Notropis and related genera (Cyprinidae, Teleostei). Environmental Biology of Fishes 33:153-165. Jordan, D. S., and B.W. Evermann. 1896-1900. The Fishes of North and Middle America. Bull. U.S. Natl. Mus. 47(1-4). 3313 pp. + 392 pls. Jordan, D.S., and C.H. Gilbert. 1883. Notes on the nomenclature of certain North American fishes. Proc. U.S. Nat. Mus. 6:1-110.

Kehmeier, J.W., R.A. Valdez, C.N. Medley, O.B. Myers. 2007. Relationship of fish mesohabitat to flow in a sand-bed southwestern river. North American Journal of Fisheries Management 27:750-764.

Knapp, F.T. 1953. Fishes Found in the Freshwaters of Texas. Ragland Studio and Litho Printing Co., Brunswick, Georgia. 166 pp.

Koster, W.J. 1957. The Fishes of New Mexico. Univ. of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque. 116 pp.

Linam, G.W., and L.J. Kleinsasser. 1996. Relationship between fishes and water quality in the Pecos River, Texas. River Studies Report No. 9. Resource Protection Division, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, Austin, Texas. 10 pp. Page, L. M. & B. M. Burr. 1991. A field guide to freshwater fishes of North America north of Mexico. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, Massachusetts. 432 pp. Platania, S.P. 1990. The ichthyofauna of the Rio Grande drainage, Texas and Mexico, from Boquillas to San Ygnacio. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 100 pp. Platania, S.P. 1991. Fishes of the Rio Chama and Upper Rio Grande, New Mexico, with preliminary comments on their longitudinal distribution. Southwestern Naturalist 36:186-193.

Platania, S.P., and C.S. Altenbach. 1998. Reproductive strategies and egg types of seven Rio Grande Basin cyprinids. Copeia 1998(3):559-569.

Propst, D.L., G.L. Burton, and B.H. Pridgeon. 1987. Fishes of the Rio Grande between Elephant Butte and Caballo Reservoir. The Southwestern Naturalist 32(3):408-411. Robinson, D.T. 1959. The ichthyofauna of the lower Rio Grande, Texas and Mexico. Copeia 1959(3):253-256. Rhodes, K., and C. Hubbs. 1992. Recovery of Pecos River fishes from a red tide fish kill. The Southwestern Naturalist 37(2):178-187. Scharpf, C. 2005. Annotated checklist of North American freshwater fishes, including subspecies and undescribed forms, Part 1: Petromyzontidae through Cyprinidae. American Currents, Special Publication 31(4):1-44. Sublette, J.E., M.D. Hatch, and M. Sublette. 1990. The Fishes of New Mexico. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque. 393 pp.

Texas Organization for Endangered Species (T.O.E.S.) (1988) Endangered, threatened, and watchlist of vertebrates of Texas. T.O.E.S. Publ. 6: 1-16.

Williams, J.E., J.E. Johnson, D.A. Hendrickson, S. Contreras-Balderas, J.D. Williams, M. Navarro-Mendoza, D.E. McAllister, and J.E. Deacon. 1989. Fishes of North America endangered, threatened, or of special concern: 1989. Fisheries 14(6):2-20.

|

||

|

|

||