|

|

||

|

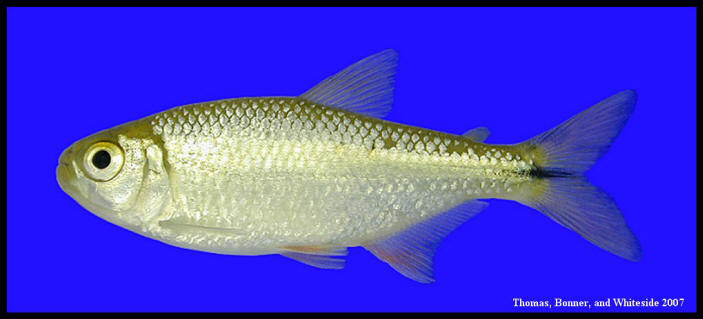

Astyanax mexicanus Mexican tetra

Type Locality "Lake near Mexico" (Filippi 1853).

Etymology/Derivation of Scientific Name Astanax- Greek for "son of Hector", mexicanus- Latin "from Mexico"(Edwards 1999).

Synonymy: A. fasciatus (Miller et al. 2005).

Characters Maximum size: 100 mm SL (Birkhead 1980; Miller et al. 2005).

Coloration: Silvery except for a black lateral band which expands near the caudal base and narrows on the caudal fin (Sublette et al. 1990). In the breeding male the dorsal and anal fins become yellowish to orange-red with fine hooklets present on the anal fins (Collette 1977).

Counts: Anal rays usually 19-23 (20-22; Miller et al 2005); 35-40 lateral scales; 10-11 dorsal rays (Page and Burr 1991).

Body shape: Oblong, strongly compressed body; head is large, laterally compressed, blunt, without scales (Sublette et al. 1991); small, minnow-like body shape (Edwards 1999).

Mouth position: Terminal (Sublette et al. 1990; Page and Burr 1991); large, strong, incisor-like teeth on jaws (Page and Burr 1991; Sublette et al 1990; Edwards 1999).

External morphology: Adipose fin (Page and Burr 1991); dorsal triangular; adipose small; pectorals and pelvic pointed, pectorals reaching pelvic base; anal long, falcate; caudal forked (Sublette et al 1990). Fine hooklets present on the anal fins of breeding male (Collette 1977).

Distribution (Native and Introduced) U.S. distribution: Louisiana, Oklahoma, Arizona (Edwards 1999); New Mexico (Sublette et al. 1990; Page and Burr 1991). Collections reported from widely separated localities such as the lower Colorado River in southwestern Arizona; Red River in and adjacent to Lake Texoma along Texas-Oklahoma border; Cross Lake in Red River drainage near Shreveport, Louisiana; and Neosho River drainageat Lake Spavinaw in northeastern Oklahoma (Birkhead 1980).

Texas distribution: Native to the Rio Grande and possibly the Nueces River drainages; has been introduced statewide by “bucket bait” release (Hubbs et al. 1991); however, there are no records of species in the Sabine Lake drainage basin in southeast Texas (Bechler and Harrell 1994; Warren et al. 2000). First found in the San Antonio River system in 1940 (Brown 1953).

Abundance/Conservation status (Federal, State, NGO) Not in danger of extinction and are not listed by governmental entities in the state of Texas (Edwards 1999). Populations in southern drainages are currently stable (Warren et al. 2000).

Habitat Associations Macrohabitat: Occupies a wide variety of habitats within native and naturalized range; found in the largest numbers in spring runs, in schools of several hundred to thousands in the swiftest currents; in small numbers in reservoirs (Birkhead 1980; Edwards 1999). In Arizona, Minckley (1973) reported Astyanax mexicanus to be a schooling species occupying a variety of habitats, including swift, flowing rapids, eddies and pools (Minckley 1973). Darnell (1962) noted species is most abundant in pool areas where they travel singly or in moderate sized school. Abundant in the more open water habitat, especially swift moving waters in the deeper channels, of the San Antonio River, Texas (Hubbs et al. 1978; Howells 1992; Edwards 2001; Gonzales and Moran 2005).

Mesohabitat: Northern distribution seems to be limited by a lack of cold tolerance (Edwards 1999); in Texas, most successful introductions have been in constant temperature springs with substantial outflows (Birkhead 1980; Hubbs et al. 1991). This species has a preference for rock and sand bottomed pools (Gonzales and Moran 2005) and backwaters of creeks and small to large rivers (Page and Burr 1991). In Waller Creek (tributary of Colorado River), Texas, young-of-year often found in shallow water, feeding near overhanging bank vegetation, while adults generally inhabited pools (Edwards 1977). Collected in pools of the Devil’s River, Texas, during the summer; common in riffles during warmer periods (Robertson and Winemiller 2003). A. mexicanus one of the community dominant species both in preflooding and postflooding conditions in southwestern Texas (Harrell 1978).

Biology Spawning season: In Waller Creek (tributary of Colorado River), Texas, breeding evident from late April-September (Edwards 1977). Reproduction occurs throughout the year in the lower Rio Grande River (Estrada 1999). Late spring and early summer (Darnell 1962; Birkhead 1980; Sublette et al 1990).

Spawning habitat:

Spawning behavior:

Fecundity: Eggs are adhesive (Sublette et al 1990).

Age at maturation: Individuals born early in the spring begin to reproduce during the autumn of their first year and continue to reproduce thereafter (Estrada 1999).

Migration: In Texas, species known to migrate to warmer environments during the winter in order to survive in areas normally considered unlikely for tetra habitat (Bechler and Harrell 1994; Edwards 1977; 1999).

Growth and population structure: Reach approximately 80 mm SL and grow at approximately 10 mm/month in lower Rio Grande River; males and females exhibit similar growth rates and there is little sexual dimorphism between males and females (Estrada 1999).

Longevity: Few individuals live longer than 2 years (Estrada 1999).

Food habits: This species is usually highly carnivorous, feeding on smaller fish, although in northeastern Mexico it has been reported to be omnivorous, with plants, filamentous algae, and aquatic insect comprising the bulk of its diet (Birkhead 1980). In the lower Rio Grande, diet includes green algae and plants, various terrestrial and aquatic insects, and occasionally fish (majority Gambusia affinis; Estrada 1999); at Phantom Springs, near Toyavale, Texas, tetras consumed similar foods as did lower Rio Grande population, although no fishes were observed in the diets of individuals from Phantom Springs (Winemiller and Anderson 1997). In each of three Balmorhea State Park environments sampled, a variety of foods were consumed, including green algae, amphipods, ostrocods, insects, crayfish, snails, and (at one site only) fish (Edwards 1999). Young-of-year observed feeding voraciously on insects, in Waller Creek (tributary of Colorado River), Texas (Edwards 1977).

Phylogeny and morphologically similar fishes This is the only characid native to the United States (Edwards 1999). Most are akin in their place in nature to the minnows of the Northern Hemisphere. The characins include the well-know piranhas of South America, but the Mexican tetra is the only native representative of the family in the U.S. (Tomelleri and Eberle 1990).

The presence of an adipose fin distinguishes the Mexican tetra from the cyprinids. The strongly compressed body and the number of scales on the lateral line (A. mexicanus 35-40; salmonids 100+) separate it from salmonids, which also have an adipose fin. Ictalurids also possess an adipose fin, however; the tetra has a scaled, strongly compressed body and lacks the conspicuous chin barbles present in catfishes. (Sublette et al.1990).

Host Records Magnivitellinum simplex, Genarchella astyanctis, Paracreptotrematina aguirrepquenoi, Ascocotyle (Ascocotyle) tenuicollis, Clinostomum complanatum, Centrocestus formosanus, Diplostomum sp., Urochleidoides strombircirrus, Gryodactylus sp., Procamallanus (Spirocamallanus) neocaballeroi, Rhabdochona mexicana, Contracecum sp., Pharyngodonidae gen. sp., Sproxys sp. (Salgado-Maldonado et al. 2004).

Commercial or Environmental Importance Astyanax mexicanus is an opportunistic invasive insectivore species that seems to be able to displace native species in ecologically stressed stream reaches (Gonzales and Moran 2005). Species used as a bait fish in the Southwest and South Central states (Sublette et al 1990). Sublette et al. (1990) note that historical records suggest A. mexicanus is one of a number of small, cold-intolerant species that once regularly migrated up the Pecos River and Rio Grande where they inhabited upstream localities until eliminated by severe winter. During subsequent high water periods in spring, species reinvaded upstream reaches from warmer downstream waters. With advent of dams, especially in the early and middle decades of the 1900’s, the pattern of upstream, cold decimation/reinvasion ended.

[Additional literature noting collection of this species from Texas locations includes, but is not limited to the following: Linam and Kleinsasser (1996); Pinto Creek (Edwards 2003).]

References Avise, J.C., R.K. Selander. 1972. Evolutionary Genetics of Cave-Dwelling Fishes of the Genus Astyanax. Evolution, Vol. 26(1):1-19. Bechler, D.L., and R.C. Harrell. 1994. Notes on the biology and occurrence of Astyanax mexicanus (Characcidae, Teleostei) in southeast Texas. The Texas Journal of Science 46(3):293-294. Birkhead, W.S. 1980 Astyanax Mexicanus (Fillipi) Mexican Tetra. pp 139 in D.S. Lee et al. Atlas of North American Freshwater fishes. N.C. State Mus. Nat. Hist., Raleigh, i-r+854. Brown, W.H. 1953. Introduced fish species of the Guadalupe River Basin. Texas J. Sci. 5:245-251. Collette, B.B. 1977. Epidermal breeding tubercles and bony contact organs in fishes. Symp. Zool. Soc. Lond. 39:225-268. Darnell, R.M. 1962. Fishes of the Rio Tamesi and related coastal lagoons in east-central Mexico. Publ. Inst. Mar. Sci., Univ. TX 8:299-365. Edwards, R.J. 1977. Seasonal migrations of Astyanax mexicanus as an adaptation to novel environments. Copeia 1977(4):770-771. Edwards, R.J. 1999. Ecological profiles for selected stream-dwelling Texas freshwater fishes II. Texas Water Development Board: 1-69. Edwards, R.J. 2003. Ecological profiles for selected stream-dwelling Texas freshwater fishes IV. Final Report to the Texas Water Development Board. 19 pp. Estrada, M. 1999. The ecology and life history of the Mexican tetra, Astyanax mexicanus, (Teleostei: Characidae) in the lower Rio Grande Valley, Texas. Unpubl. M. S. thesis, The University of Texas-Pan American, Edinburg, TX, 53 pp. Filippi. 1853. Nouvelles espèces de poisson. Rev. Mag. Zool. [Ser. 2] 5:166. Gonzales, M. and E. Moran. 2005. An inventory of fish species within the San Antonio Missions National Historical Park. San Antonio River Authority, Final Report. Harrell, H.L. 1978. Response of the Devil’s River (Texas) fish community to flooding. Copeia 1978:60-68. Howells, R.G. 1992. Annotated list of introduced non-native fishes, mollusks, crustaceans and aquatic plants in Texas waters. Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, Manage. Data Ser. 78:1-19. Hubbs, C., T. Lucier, G.P. Garrett, R.J. Edwards, S.M. Dean, and E. Marsh. 1978. Survival and Abundance of introduced fishes near San Antonio, Texas. Texas J. Sci. 30:369-376. Hubbs, C., R. J. Edwards, and G. P. Garrett. 1991. An annotated checklist of the freshwater fishes of Texas, with keys to identification of species. Texas Journal of Science, Supplement 43(4):1-56 Linam, G.W., and L.J. Kleinsasser. 1996. Relationship between fishes and water quality in the Pecos River, Texas. River Studies Report No. 9. Resource Protection Division. Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, Austin. 11 pp. Miller, R.R., W.L. Minckley and S. M. Norris. 2005. Freshwater Fishes of Mexico. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 490 pp. Mills, D. and G. Vevers. The Tetra Encyclopedia of Tropical Freshwater Fishes. Morris Plains: Tetra Press, 1989. Minckley, W.L. 1973. Fishes of Arizona. Phoenix, Arizona Game and Fish Department 293 pp. Page, L.M. and B.M. Burr. 1991. A Field Guide to Freshwater Fishes of North America, north of Mexico. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, 432 pp. Robertson, M.S., and K.O. Winemiller. 2003. Habitat associations of fishes in the Devil’s River, Texas. Journal of Freshwater Ecology 18(1):115-127. Salgado-Maldonado, G., G. Cabañas-Carranza, E. Soto-Galera, R. F. Pineda-López, J. M. Caspeta-Mandujano, E. Aguilar-Castellanos and N., Mercado-Silva. Helminth 2004. Parasites of Freshwater Fishes of the Pánuco River Basin, East Central Mexico. Comp. Parasitol. 71(2):190-202. Sublette, J.E., M.D. Hatch, M. Sublette. 1990. The Fishes of New Mexico. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 393 pp. Tomelleri, J.R. and M.E. Eberle. 1990. Fishes of the Central United States. University Press of Kansas. Lawrence. 226 pp. Warren, M.L. Jr., B.M. Burr, S. J. Walsh, H.L. Bart Jr., R. C. Cashner, D.A. Etnier, B. J. Freeman, B.R. Kuhajda, R.L. Mayden, H. W. Robison, S.T. Ross, and W. C. Starnes. 2000. Diversity, distribution and conservation status of the native freshwater fishes of the southern United States. Fisheries 25(10):7-29. Winemiller, K.O., and A.A. Anderson. 1997. Response of endangered desert fish populations to a constructed refuge. Restoration Ecology 5:204-213.

|

||

|

|

||